Regulation (Tax): Esports from a tax perspective

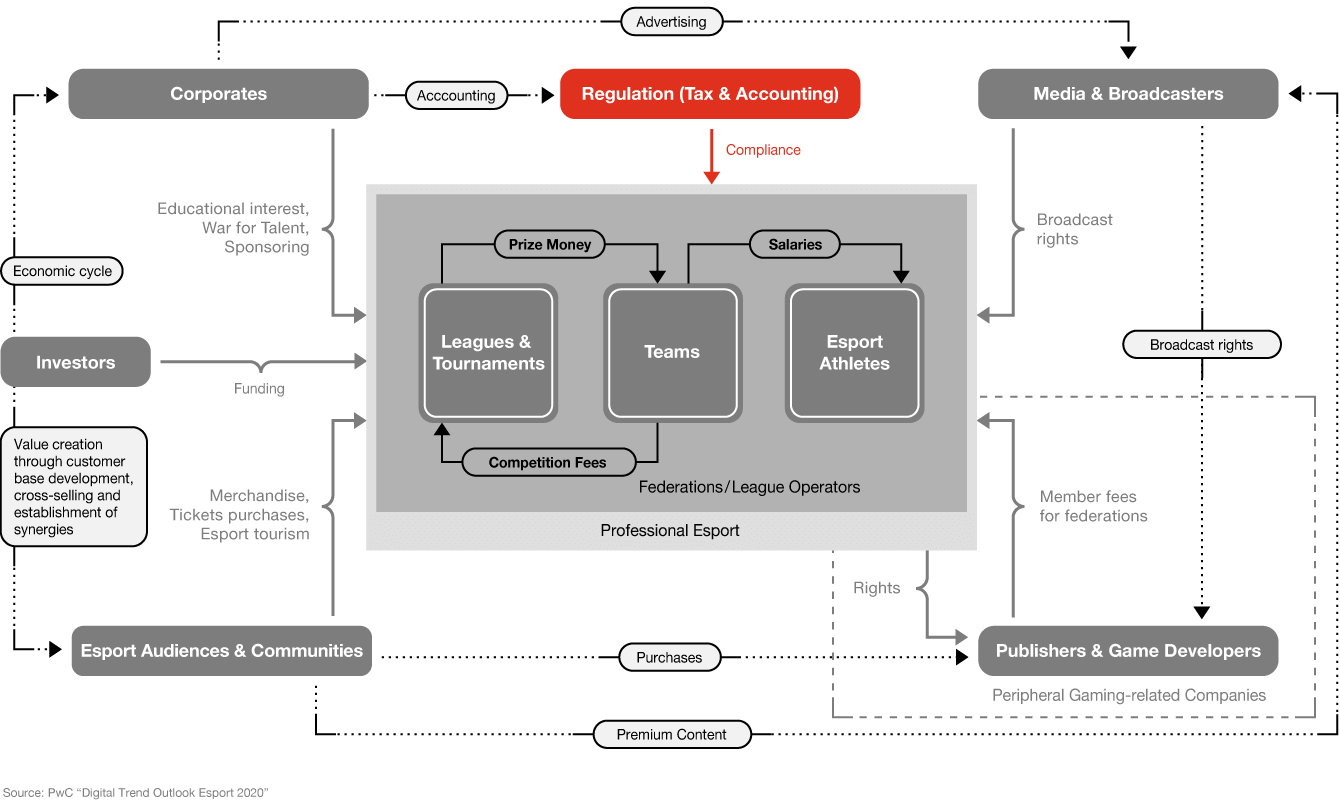

By Swantje Groth, Stefan Kämmerer. Esports has developed from a niche to serious business, growing at an accelerating speed in recent years. Whereas tax law tries always to adapt to new developments and circumstances, it cannot by nature keep up with the speed. Traditional taxation principles refer to physical presence as a general requirement for a nexus of taxation for companies. However, digitalization breaks domestic borders, allows international expansion into new markets and facilitates cross-national collaboration without having any physical presence in such foreign countries. As a result, states are loosening up the requirements to deem a physical presence or even implement new taxation principles to claim their fair share of taxes on the profits generated. Despite ongoing multilateral negotiations by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

to harmonize the tax principles for the digital sector, several countries have moved ahead with unilateral measures, creating huge challenges for digital companies like league operators and game publishers when it comes to monitoring international tax developments and keeping pace with different local tax authorities to ensure their tax compliance in the respective countries. This is particularly true for the esports industry. This tax chapter aims to provide an overview of certain selected tax issues and challenges related to esports that are relevant not only for game publishers, but also for gamers, league operators and sponsors. It starts with the taxation of gamers before discussing issues for egaming companies such as game publishers.

Esports gamers in the tax world

Gamers can be separated in two groups. The first group consists of casual gamers, who enjoy a game and buy in-game content without receiving any (monetary) remuneration. They are highly crucial for the success of games, as an increasing player base attracts new gamers, which in turn boosts the fan base and eventually revenue. For these gamers, the tax consequences — such as VAT and sales tax for the purchase of in-game currency — are mostly irrelevant because the occurring tax issues are handled by game publishers, game distributors and payment service providers. Related corporate tax and VAT aspects are dealt with later on in this chapter.

This section focuses on the second group of gamers, consisting of (semi-)professional players who are paid for or receive benefits from playing games. This group is a rather heterogeneous group, with remuneration ranging from small compensation for providing occasional in-game community support to huge wins of seven-digit prize money from competing in tournaments. This remuneration might be accompanied by sponsors entering the market, supporting the players with payments in kind (such as hardware) in addition to cash compensation.

For German-resident gamers playing on an independent basis, the income received will usually be subject to personal income taxation as trading income (gewerbliche Einkünfte) in Germany. Often, esports gamers are organized in professional groups, such as clans or guilds, with an employment contract in place. In those cases, the income will qualify as income from dependent employment (Einkünfte aus nichtselbständiger Arbeit). Basically, both types are subject to general income taxation, but the level of complexity, documentation and filing requirements is usually much lower for the second type of income, as the employer is usually in charge of withholding wage taxes on the salaries paid. For the first type, any benefit received should be properly documented and reported in tax returns to avoid nasty surprises involving inquiries from the tax office. Complexity increases, requiring an individual analysis, in case esports gamers receive income in different countries, e.g. from participating in foreign tournaments - either virtually or by being physically present. Players who are aware of local fiscal rules and regulations in the respective countries can avoid potential risks or non-compliance penalties and also have the chance to address and solve potential double-taxation issues early (i.e. if the same income is taxed in two states).

Particular attention should be paid if these players are sponsored by external parties. Usually, benefits received represent taxable income and need to be declared in the tax return. This is also true if the benefits are paid as a benefit in kind (such as computers or gaming equipment). Yes, taxes still need to be paid although no cash is received.

In addition, gamers need to be aware of their VAT obligations if they are not working under an employment contract. Examples are entrance fees paid to the gamers for taking part in a specific competition, which may be subject to VAT. Tax law qualifies the participation of gamers as a service in return for the joining bonus paid, requiring the gamer to remit VAT on the fees received. Similarly, if the gamer promotes sponsored products, VAT might also apply on the remuneration received from the sponsor. As marketing service recipients in these cases, sponsors should also keep in mind that a formally correct invoice from the gamer is required to allow input VAT deduction. Assessing the tricky tax base for VAT purposes may prove challenging if the remuneration is a payment-in-kind or — even worse — a barter transaction rather than cash.

The good news at the end: Prize money for winning a tournament is usually not subject to VAT but - of course - to income tax.

Global tax environment for game publishers and league operators—opportunities and risks

The key to success, and most important the asset of game publishers, is intellectual property (IP) in terms of (self-developed) games. Similarly, league operators sell or license IP in the form of participation slots in franchise league systems, for example. Because of its intangible character and flexibility, IP presents opportunities for tax restructuring and tax planning. On the other hand, the structuring possibilities are contrasted by the political and public demands for the responsible and fair taxation of companies.

The development of new games or league systems is not only very expensive, but also risky, as it cannot be foreseen whether the respective game or tournament will become a future blockbuster or — more likely — a failure. Considering the significant investments and costs, it can be attractive to create the intangible assets in a country with high tax rates in order to achieve the best possible tax deductions. Concurrently, the taxation of the future profits generated should be considered as well, making a low-tax regime or special IP regime preferable.

Many OECD countries have introduced special tax rules and IP regimes to attract new digital businesses and promote the development of IP in their countries, thereby gathering knowledge and specific IT expertise, which in turn creates jobs and future tax revenues. Tax incentives vary between special lower tax rates for profits generated with (self-developed) IP, tax credits for research and development expenses or additional tax base deduction of development costs, making it very attractive for publishers to (re-)locate their games and IP to those jurisdictions. However, not all IP incentives are also available for game publishers or league operators to boost their development activities and need to be scrutinized.

Another important aspect is the reputational risk attached to the (re-)location of games and connected intangible assets, though there is generally nothing illegal about IP restructuring, and it is even intended for and used by governments as incentive to attract new businesses—provided, of course, that no artificial or abusive scheme is in place. Given the increasing public interest in digital companies and reporting in the media about tax evasion, publishers should be very sensitive about their IP structure to avoid frightening off stakeholders, including gamers, sponsors and employees.

The ongoing and envisaged changes in the taxation of the digital economy will affect publishers, league operators and probably the framework for future tax planning. New reporting obligations have already been implemented within the EU and become effective in the member states in 2020, requiring notification of the tax authority in case of cross-border tax restructurings (DAC 6). Non-compliance can lead to severe fines. This is accompanied by strict rules, triggering exit taxation in case of a cross-border relocation of games, for example. In the absence of an arm’s length sale transaction, the (usually high) fair market value of the games will be revealed and subject to full taxation, imposing a heavy cash tax burden on the publisher. Publishers may also unintentionally expose themselves to these risks due to actions such as the relocation of the employees or teams who are in control of game development or the continuous improvement and creation of in-game content. The same holds true for league operators. Therefore, digital companies should be aware of their games and the location of IP rights, as well as the contractual basis, which should be continuously reviewed and properly documented.

As a general rule, taxes should follow business operations and not the other way around. If companies are located in countries with higher-tax regimes, the taxes paid in such countries could be used as an efficient marketing instrument, demonstrating local engagement and connectedness, and thereby attracting new employees and customers. For a lot of companies, it is no longer about how taxes can be minimized but rather about compliance with local and multinational obligations, as well as paying their fair share of taxes and contributing to society.

Game development in Germany—searching for tax benefits with a magnifying glass

At 29.9% on average, Germany has one of the highest effective corporate tax rates of any OECD state. Within the EU, only three countries had higher tax rates on corporate profits as of 2019, according to a study on the most important taxes in international comparison from the German Federal Ministry of Finance.

The Research Allowance Act (Forschungszulagengesetz) may provide some relief. Starting from January 1, 2020, Germany introduced a tax credit (“research allowance”) for certain research and development (R&D) projects with a funding rate of 25% on eligible personnel costs and costs for contract research. This new funding instrument allows a support of up to €1 million per corporate group and fiscal year. In contrast to direct project funding in Germany, this funding is not taxable. To benefit from the research allowance, the R&D activities must qualify either as fundamental research, industrial research or experimental development, restricting the potential eligible projects under this program. For game publishers, especially the areas of industrial research and experimental development could be relevant. However, the application forms have not yet been published and it is currently unclear, which requirements need to be fulfilled exactly to benefit from the research allowance. Nevertheless, this can be seen as a starting point, improving the attractivity of Germany as a location for development activities.

Outside the tax world, the German game industry has already reached a higher level of awareness in politics, successfully securing €50 million a year in funding from the German government until 2023 to support the development of games in Germany (expected total volume of €250 million). The pilot phase was already launched last year for smaller projects with up to €200,000 of funding per project (De-minimis-aid). The second stage of the funding programme is currently under preparation.

With regard to taxation, the lucky recipients under the game funding program may feel a slight sense of disappointment, as it is necessary to monitor if and when those subsidies are subject to taxation. Additional questions may arise if the taxable income from the subsidy can be equally distributed over the development period or already represents taxable income upon receipt.

A minor benefit can be found when looking at the development expenses in Germany. Whereas self-developed games are classified as intangible assets in the balance sheet and costs are capitalized, German tax law allows the immediate tax deduction of the development costs as operating expenses. This implies that the costs incurred directly reduce the tax burden of the respective year, resulting in a positive cash flow effect (provided the company is already in a profit-making situation). If the company is still in the start-up phase and generating losses, tax loss forfeiture rules should be kept in mind when new investors are ready to join and invest. In case more than 50% of the shares in the company are transferred, the tax losses will principally be forfeited and cannot be used anymore to offset future taxable income. However, exemptions are available and should be carefully reviewed in detail before shares are transferred.

Additional tax issues that need to be monitored refer to partial non-deductibility (trade tax add-backs) of rent for movable property, especially servers, or for the use of rights, such as specific figures or graphics. In case of the latter, withholding tax impacts could arise if the IP and rights are licensed from a licensor outside Germany.

International tax compliance challenge—getting ready for the next level

Game publishers, league operators and esports clans operate internationally. As a result, they are subject to different local tax regimes and need to comply with local tax filing, reporting and payment obligations. However, the rules vary significantly between the countries. The speed at which changes in tax law systems are implemented is also increasing, begging the question: Is it possible to be tax compliant in all countries?

Level 1: Handling your limited corporate tax liabilities in foreign jurisdictions

In order to become subject to limited tax liability in a certain country, some kind of a local nexus for taxation is required. This nexus is usually established in the form of a fixed place of business — creating a permanent establishment — with the exact criteria depending on the respective tax law of that jurisdiction and the applicable double-tax treaty, if any. Common examples are offices, factories or branches.

Less-known examples are servers, which might be qualified by tax authorities in some jurisdictions as a fixed place of business, requiring the non-resident entity to file local tax returns and eventually allocating a portion of the profits to the country where it will be subject to local taxation. Caution should also be applied to home offices and the like, which could also be relevant for professionally employed gamers or game developers that have all their technical equipment at home.

A recent example illustrates that a nexus for corporate taxation can be established without having any physical presence or employees in the country in question. Several digital companies have received a letter from the Turkish Ministry of Treasury and Finance, announcing that the respective entity has a nexus for taxation by having a Turkish website through which revenue is generated. While this one-sided approach will lead to controversial discussions, it is a clear indication of where some jurisdictions are heading.

Another type of foreign taxes are withholding taxes, which are directly withheld by the paying party. Often, withholding taxes are levied on the use of rights for a certain limited time, such as license payments from league operators to game publishers for allowing the league operators to organize an electronic sports league for the specific game. Other examples are the broadcasting or streaming rights paid to game publishers or league operators. When rights are licensed, the availability of double tax treaties and unilateral measures should be reviewed in advance to avoid potential risks of double taxation.

As a result, companies should be sensitive to all their foreign activities and keep track of any changes that might trigger a nexus for taxation to complete level 1.

Level 2: Foreign value added tax (VAT) and sales tax obligations on digital services

VAT obligations are one of the key issues to be taken into account when game developers, league operators or media companies offer their digital products to individual customers (known as business to consumer services, or B2C) in foreign countries. Common examples are the sale of in-game content or virtual goods and currencies.

For instance, a physical presence is no longer required to become subject to US sales tax, since a sales tax liability is nowadays linked to the economic nexus. The sales tax liability in the US states therefore depends on the volume of domestic sales or the number of transactions within a certain period. Furthermore, there are no uniform sales and transaction thresholds between the states, making it complex for service providers to track the thresholds in each state.

Besides the US, many other countries charge VAT on digital services if certain revenue or transaction thresholds are exceeded, which means that companies have to deal with the specific requirements of each country and may have to register for VAT or even appoint a fiscal representative in those countries.

To pass this level, you need to report the revenue and number of transactions in each country or state in which digital B2C services are provided. Any concerns with local VAT registration obligations?

Level 3: Monitoring wage tax and social security aspects

Digitalization improves collaboration with freelancers such as developers, professional gamers and designers for certain development projects or as community support within online games. When freelancers are engaged, wage tax and social security aspects should be monitored. If, for example, a seemingly independent developer works for a publisher and supports the publisher in managing in-game content on a comprehensive basis, it is possible that the developer might be deemed as pseudo self-employed (depending on the details of the particular case) and will be requalified as an employee of the game publisher. The wrong qualification will result in wage tax and social security payments by the economic employer, which could easily reach substantial amounts if the pseudo self-employed freelancer was engaged for a longer period of time.

General criteria for the qualification as self-employed are whether the person has a certain entrepreneurial freedom of decision, bears the entrepreneurial risk, is not organizationally involved in the client’s business, can independently determine the place and time of performance and has the possibility of working for several clients.

The criteria for deemed self-employment as well as the underlying wage tax and social security consequences vary among the different jurisdictions and usually require a local analysis. In order to minimize potential tax exposures, engaged freelancers should be analyzed in this respect to pass this level.

Boss level—be prepared for new rules before they become effective

In order to assess whether local tax filing obligations arise, the relevant data needs to be obtained first. Often, the required data cannot be automatically extracted from the IT systems but needs to be tediously gathered by employees, binding already very limited capacities in tax and finance departments that are also needed elsewhere. Anticipating potential changes in tax law systems enables taxpayers to adjust their IT and reporting systems early to have the relevant data available, being prepared when legal changes become effective. An example is the tracking of revenue and the number of transactions in each of the 50 US states for the US sales tax filing obligations that were required within a short period of time after a surprising decision in a US Supreme Court case back in 2018.

If you like challenges, try the newly introduced digital services tax, which has been unilaterally enacted by some OECD countries, such as Austria and France, without awaiting a harmonized and aligned solution at OECD level. In France, the digital services tax became applicable with retroactive effect as of January 2019 and aims to tax revenue (not profit!) from digital services, especially targeted advertising services based on user profiles and intermediation services, the supply of digital interfaces that enable users to interact with each other. The question arises as to the part of the relevant global revenue that will be allocated to France, the criteria on which such decisions will be based (such as the users in France in relation to the total number of users) and the way such information can be summarized. For the moment, the digital services tax applies only to companies that, at a consolidated group level, provide certain digital services localized in France with global annual revenue exceeding €750 million in taxable services and €25 million thereof in France, which narrows down the circle of affected entities to big multinational groups and corporations.

If your digital business is not affected by this tax, consider yourself lucky. But putting yourself in the shoes of those companies, would you be able to analyze them and provide the relevant data on time? If yes, you successfully complete the boss level.

Contact us

Werner Ballhaus

Global Leader Entertainment & Media, Partner, PwC Germany

Tel: +49 211 981-5848

Contact us

Werner Ballhaus

Global Leader Entertainment & Media, Partner, PwC Germany

Tel: +49 211 981-5848